Originally written in Fall 2020 for my Pandemics and Cities course.

This summer while I was taking courses online for the first time, I shared a couple school reports on my social media. They were received well by my friends, family, and former colleagues, so I thought I’d keep it up. Right now I am finishing up my degree in Global Environmental Systems. I have the privilege of being able to take electives of any kind to get the last few credits done, and one of them is a special topics course called Pandemics and Cities. It has been an eye-opening, practical urban planning course which allows students to look at what’s happening on earth right now and to explore it through a sustainable development lens.

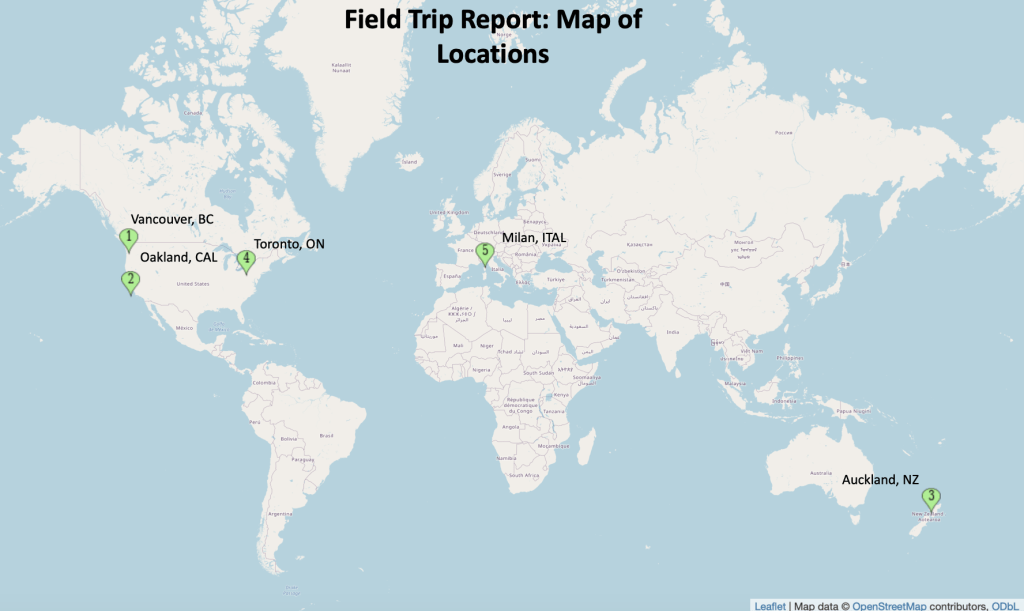

The following “field trip report” asks us to virtually explore five locations, either in the same city or multiple, and explain how COVID-19 has affected the urban landscape. I chose to expand on a topic I have already done a project on this term, which is the transformation of streets.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen cities across the world transform. Urban populations are the densest and are most impacted by the virus, so their streets have had to adapt. In this field trip report, I continue on the theme of my seminar: Planning and Design. I outline the responses of five developed cities across the world to implement changes to the streets specifically. How streets are used during this pandemic could inform the way we want to live in a more sustainable way in the future. The role of municipal urban governments is key to resiliency, because how it copes with a crisis is related to its urbanization choices (Chatterji and Kamiya, 2020).

Map of Locations

Case 1: Vancouver

Compared to many North American cities, Vancouver is a relatively transit-friendly and bikeable city. The onset of COVID-19 going into the spring transformed many of its streets, and this persists as winter arrives. One of the most noticeable differences on the streets is the parklet and pop-up plaza program. The sidewalk and curb area is expanded on a number of city streets to allow people to distance outside while still enjoying a meal or drink from adjacent businesses hit hard by the pandemic. It also serves to maintain socialization and a sense of community with very little energy use. Although parklets and pop-up plazas have been implemented in Vancouver since 2011 (City of Vancouver, 2020), COVID-19 has accelerated their appearance, and are even being extended into the fall (Bains, 2020).

Case 2: Oakland

Oakland, California has a population of about half a million. It took a bold step to transform twenty miles of streets into “Slow Streets”, and to designate fifteen “Slow Street Essential Places”. These sites are given safety improvements, providing residents safer access to grocery stores, food distribution sites, and COVID test sites (City of Oakland, 2020). Importantly, they have released an interim report to let people know how the program has done. In particular, they acknowledge the “realities of Oakland’s inequitable distribution of resources and opportunities, and the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on Oakland’s Latinx and Black communities” (City of Oakland, Sept 2020). This is an intersectional lens which all cities need to consider while transforming their streets during and after the pandemic. While many urban improvements are being accelerated, the pandemic is also revealing structural and institutional inequities seen though racialized death rates (Enns and Marazzi, 2020). Oakland continues to be shaped by carcerality, surveillance, and racial power relations on the borderlands (Ramirez, 2019). The interim findings conclude that the slow streets were positively received mostly by higher income white residents, but essential workers and marginalized groups felt it wasn’t meeting their needs. The city is considering making context-specific local changes, continuing the program during the pandemic.

Case 3: New Zealand

New Zealand has been praised for its fast mobilization of urban space changes at the outbreak of COVID-19, providing funding from a national level. Their transport agency aimed to make walking and cycling more feasible by funding pop-up bike lanes and wider sidewalks, and were one of the first countries to do so this year. In Auckland (pop 1.4 mil), many pop-up bike lanes were installed and car parking has been removed from one side of several streets to allow more open-air activities (Kamin, 2020). Transport Minister Julie Anne Genter describes it as a form of tactical urbanism, which has been attempted in New Zealand before, but accelerated by the pandemic. The benefit of these strategies is they can be locally tailored and implemented in hours or days. Genter hopes communities will want to see them implemented permanently:

“When we move out of the shutdown, and people start to travel a little more, we can’t expect them to go back to crowded buses and trains at the same rate, and people in city centres will need more space to distance themselves from others physically” – Julie Anne Genter (Reid, 2020).

Case 4: Toronto

Several months ago, Toronto decided to close some major roads to cars on weekends, making space for cyclists and pedestrians. They have also implemented several quiet streets. When the economy started to open up again recently, there were some major traffic issues on these streets, but the program has been well received overall. The ActiveTO program has been expanded into October 2020 even though it was set to end in September (City of Toronto, 2020). On average weather days, an average of 18 000 cyclists and 4 000 pedestrians used the new lanes on Lake Boulevard West this summer (Smith, 2020). A preliminary survey of the quiet street program shows that “many people have found the program beneficial for purposes beyond COVID-19 response management and hope that it can evolve into something more” (City of Toronto, 2020).

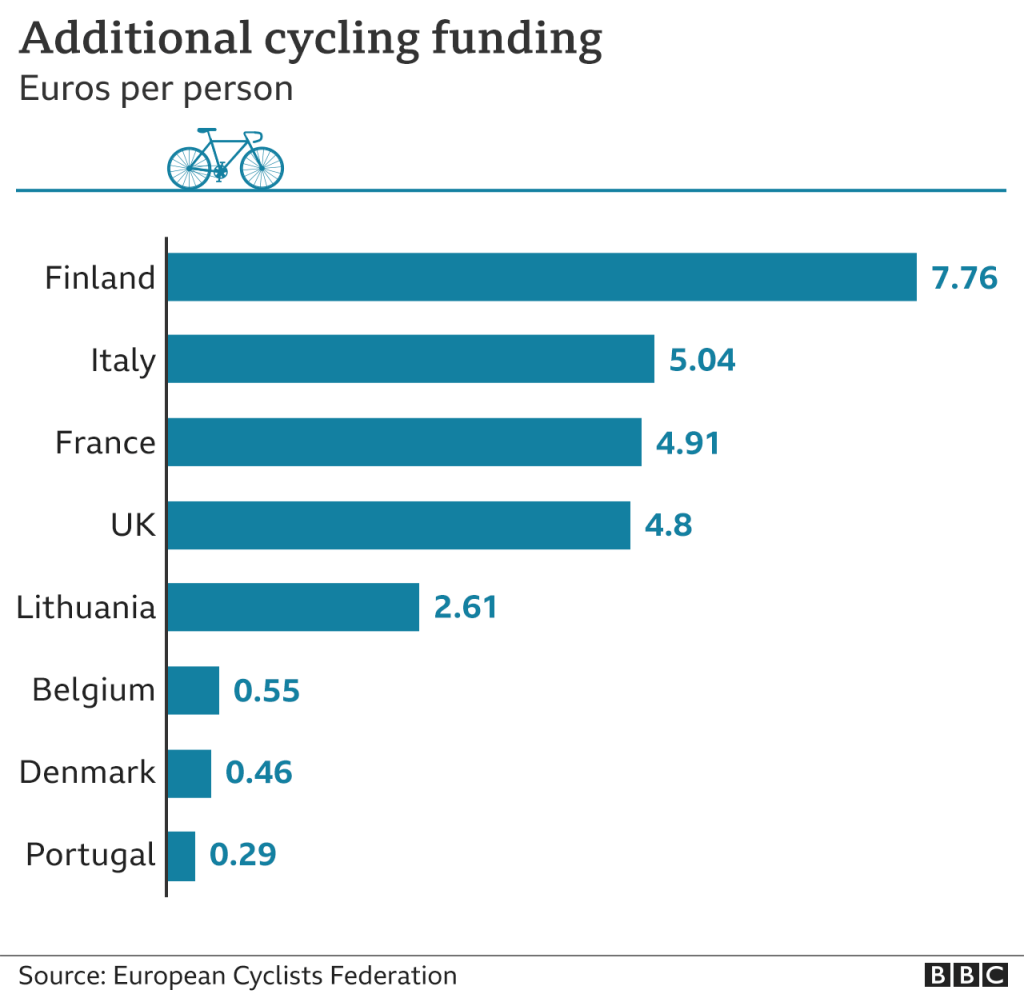

Case 5: Milan

Milan, Italy has set an international example for transforming their city during COVID-19. Italy was one of the hardest-hit countries early in 2020, so it was ideal to push for street reorganization. Previous resistance against adding bike lanes is now overruled by the need for more active transportation during the pandemic. Milan installed thirty-two kilometers of new cycle paths, though many of them are intended to be temporary (Vandy, 2020). It is not a perfect system, which is understandable because of how quickly it was implemented, but it has the potential to inspire the future of Milan’s streets. Environmental lawyer Anna Germotta believes the “coronavirus is a moment in which every policy maker can change their own cities” (Vandy, 2020)

Conclusion

The urban shift we are witnessing during the pandemic indicates the beginning of a wave, one of improving cities by enriching their public spaces. The acceleration of implementing bike lanes, expanded sidewalks, parklets, plazas, and other open-air facilities will prioritize green transportation and resiliency. The way to achieve this is for us all to vouch for pedestrian and cycling spaces in our cities, making our voices heard by municipal and provincial/state governments. We should also be implementing grassroots, tactical projects on our streets to makethem safer and more connected during such difficult times. As the northern hemisphere enters its next cold winter, it will be important to see how cities like Vancouver will accommodate its homelessness, address the opioid crisis (which kills more than COVID-19), and address racial inequality which shapes the city itself.

—

Reference List

Bains, Meera. “3 Metro Vancouver Cities Vote to Extend Temporary Patio Season into Winter Due to Pandemic” CBC News, 17 Sept. 2020, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/patio-season-extended-1.5727470.

Bliss, Laura. “How Coronavirus Is Reshaping City Streets.” Bloomberg, 3 Apr. 2020, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-03/how-coronavirus-is-reshaping-city-streets.

“COVID-19: ActiveTO – Closing Major Roads.” City of Toronto, 6 Oct. 2020, http://www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-protect-yourself-others/covid-19-reduce-virus-spread/covid-19-activeto/covid-19-activeto-closing-major-roads/.

“COVID-19: ActiveTO – Quiet Streets.” City of Toronto, 1 Oct. 2020, http://www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-protect-yourself-others/covid-19-reduce-virus-spread/covid-19-activeto/covid-19-activeto-quiet-streets/.

Enns, Cherie, and Mikayla Marazzi. “Reset City: A Response to COVID-19.” Planning West, 2020, pp. 12–14.

“How the COVID-19 Crisis Can Reinvent Roadways.” U.S. News & World Report, http://www.usnews.com/news/cities/articles/2020-07-21/how-the-covid-pandemic-can-change-cities-for-the-better.

Kamin, Debra. “These Cities Are Becoming Much More Pedestrian-Friendly.” Condé Nast Traveler, 2 July 2020, http://www.cntraveler.com/story/these-cities-are-becoming-much-more-pedestrian-friendly.

Kamiya, Marco, and Tathagata Chatterji. “Why We Need a New Social Contract for Our Cities.” ORF, 5 Oct. 2020, http://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/why-we-need-new-social-contract-our-cities/.

Kimmelman, Michael. “The Great Empty.” The New York Times, 23 Mar. 2020, http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/23/world/coronavirus-great-empty.html.

“Oakland Slow Streets.” City of Oakland, http://www.oaklandca.gov/projects/oakland-slow-streets.

“Oakland Slow Streets Interim Findings Report, September 2020.” City of Oakland, http://www.oaklandca.gov/documents/oakland-slow-streets-interim-findings-report-september-2020-1.

“Parklet Program.” City of Vancouver, vancouver.ca/streets-transportation/parklets.aspx.

Ramírez, Margaret M. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 38, no. 1, 2019, pp. 147–166., doi:10.1177/0263775819843924.

Reid, Carlton. “New Zealand First Country To Fund Pop-Up Bike Lanes, Widened Sidewalks During Lockdown.” Forbes, 15 Apr. 2020, http://www.forbes.com/sites/carltonreid/2020/04/13/new-zealand-first-country-to-fund-pop-up-bike-lanes-widened-sidewalks-during-lockdown/#1dff6c77546e.

Roberts, David. “How to Make a City Livable during Lockdown.” Vox, 13 Apr. 2020, http://www.vox.com/cities-and-urbanism/2020/4/13/21218759/coronavirus-cities-lockdown-covid-19-brent-toderian.

Smith, Ainsley. “A Number of Major Roads Are Going to Be Closed in Toronto This Weekend.” Toronto Storeys, 25 Sept. 2020, torontostoreys.com/toronto-road-closures-september-26-27/.

Vandy, Kate. “Coronavirus: How Pandemic Sparked European Cycling Revolution.” BBC News, 2 Oct. 2020, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54353914.

One thought on “The transformation of streets during COVID-19”