This is an exerpt from a term-long “walkabout” journal from my Indigenous Perception of Landscape course. This was from week two, and I am particularly keen to share all the interesting things I found out about my own back yard.

Walkabout 2 – Neighbourhood presence

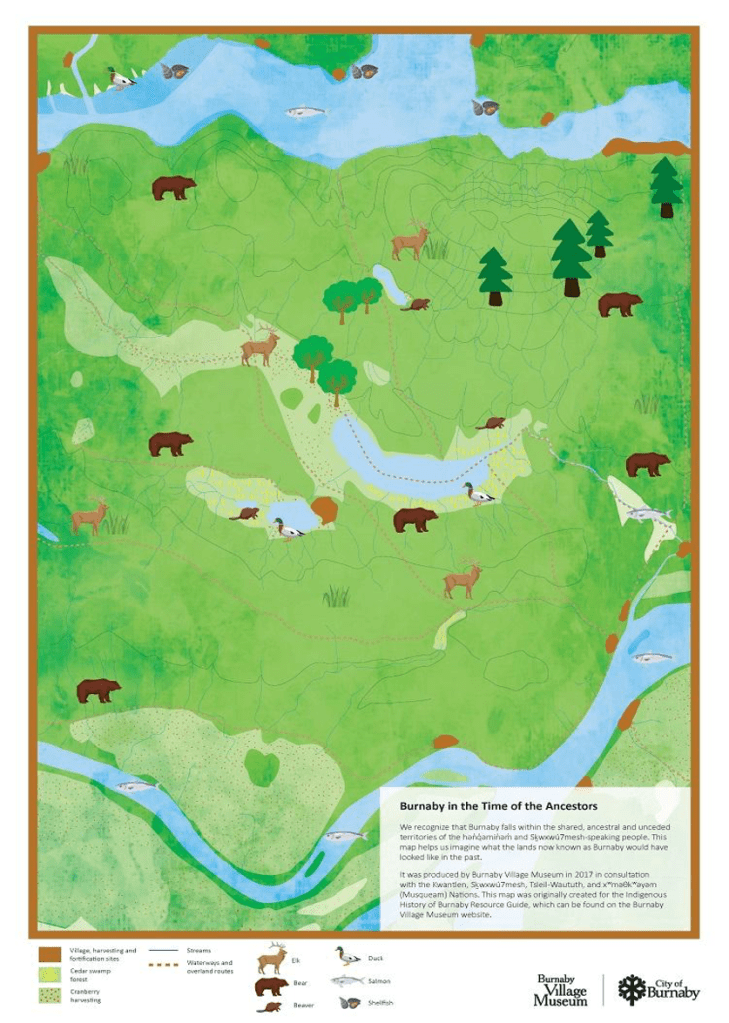

In lecture this week we learned that when Burnaby was delineated and named, it was named after a settler industrialist. Colonial names like this are reflected in almost all of the streets in the whole city. On Google Maps, I took a more thorough look at my surrounding neighbourhood in the Metrotown/Deer Lake area, and I couldn’t find a single street name with an ‘obviously’ Indigenous name. Now, it is possible that I am not aware of a certain street name referencing an Indigenous person’s colonial name or something similar. Most of the streets are settler names or are simply descriptive (ex. Eastlake). Throughout my whole life I have walked all around my area, even more so during the pandemic. I have trouble thinking of any examples of art, monuments, or community gathering places which have Coast Salish origin or influence. What is now called Burnaby has many interesting Indigenous histories and an archaeological record. Much of this information was published by the Burnaby Village Museum in 2019 in a resource guide called Indigenous History In Burnaby. It collects a great amount of information on the cultures, living patterns, and land use of the Indigenous peoples living here throughout the millennia. It also discusses the discrimination of the Indian Act and other efforts by Canada to inflict cultural genocide.

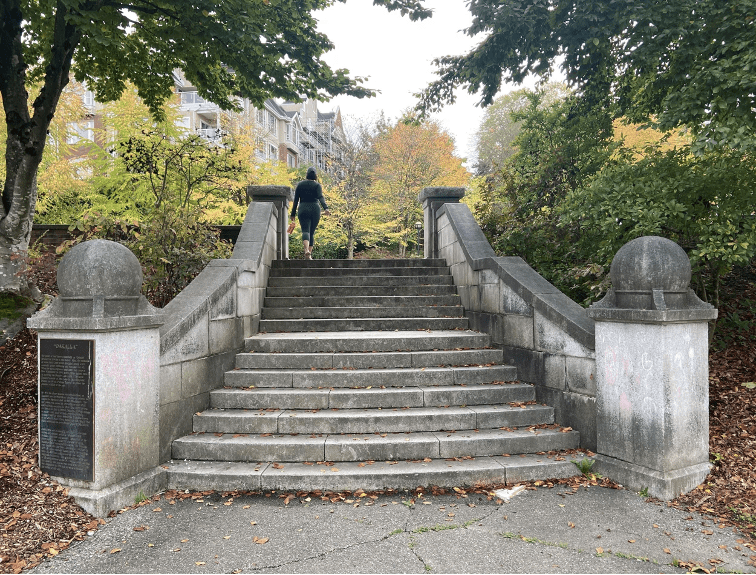

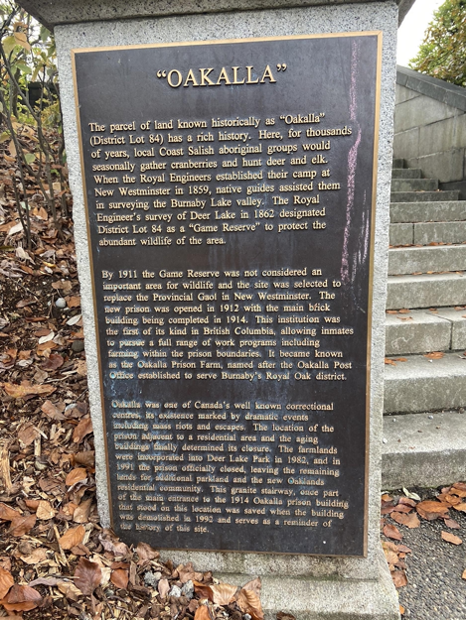

There were no residential schools in Burnaby, but I want to discuss something in the same realm of carcerality and discrimination: the Oakalla Prison Farm. Up a steep slope on the south side of Deer Lake, there used to be a prison complex. Today it is a sprawling area of townhouses and apartments, intersected down the middle by hundreds of stone steps. Many Burnabarians walk around the park paths, and locals like me often walk up the many stairs for a good workout. They lead from the lake marsh area all the way up to a busy street at the top of the hill. Deer Lake Park is a beautiful area which I enjoy so much. I’m glad the city works to keep its biodiversity somewhat managed; you can often see turtles, frogs, and the iconic Great Blue Herons in between the reeds and deciduous trees. It gives a small glimpse into what the landscape may have looked like before contact and development which has taken place in the last couple centuries. Luckily, a good amount of the natural riparian land was preserved and restored from its previous use for farming at the prison. The Oakalla prison is not something you’d see any evidence of, if not for the two plaques next to the original stone stairs from the prison entrance (see images below). Here is a transcription of the older 1992 plaque, which is a very settler-oriented perspective as I will discuss afterwards:

“OAKALLA”

The parcel of land known historically as “Oakalla” (District Lot 84) has a rich history. Here, for thousands of years, local Coast Salish aboriginal groups would seasonally gather cranberries and hunt deer and elk. When the Royal Engineers established their camp at New Westminster in 1859, native [sic] guides assisted them in surveying the Burnaby Lake valley The Royal Engineer’s survey of Deer Lake in 1862 designated District Lot 84 as a “Game Reserve” to protect the abundant wildlife in the area.

By 1911 the Game Reserve was not considered an important area for wildlife and the site was selected to replace the Provincial Gaol in New Westminster. The new prison was opened in 1912 with the main brick building being completed in 1914. This institution was the first of its kind in British Columbia, allowing inmates to pursue a full range of work programs including farming within the prison boundaries. It became known as the Oakalla Prison Farm, named after the Oakalla Post Office established to serve Burnaby’s Royal Oak district.

Oakalla was one of Canada’s well known correctional centres, its existence marked by dramatic events including mass riots and escapes The location of the prison adjacent to a residential area and the aging buildings finally determined its closure. The farmlands were incorporated into Deer Lake Park in 1982, and in 1991 the prison officially closed, leaving the remaining lands for additional parkland and the new Oaklands residential community. This granite stairway, once part of the main entrance to the 1914 Oakalla prison building that stood on this location was saved when the building was demolished in 10992 and serves as a reminder of the history of this site”

There is a lot which could be unpacked, fact-checked, and critiqued from this 1992 plaque, but I want to focus on the Indigenous perspective of this particular landscape. The plaque mentions that Coast Salish peoples (not being specific to which groups) gathered in this Deer Lake area. Some middens have been found near the lake, just an inkling of what human activity occurred there over thousands of years (BVM Resource Guide). What is ironically not mentioned on the plaque is that the Oakalla prison held Indigenous peoples for resisting threats to their land, government, and cultural practices between 1912-1991. One example was being imprisoned for conducting Pot Latches, which were illegal under the Indian Act for many years. For this walkabout I took a hike around the lake and up the stairs, ending at the prison site. I reflected on what occurred there, and pondered the dichotomy of the stone steps next to a children’s playground. Many people walk and play there, not knowing what terrible memories are embedded in the landscape. The only story I had previously known about the prison was that when my dad was young, he would go with his friends and galivant around the abandoned buildings. He passed away when I was a teenager, but I would be interested today to ask him what it was like inside, if he felt any remorse, or if he even knew what happened there. Tens of people were executed there when capital punishment was still legal. There’s a lot more I could research on this fascinating place, but I want to focus on the Indigenous presence, or lack thereof.

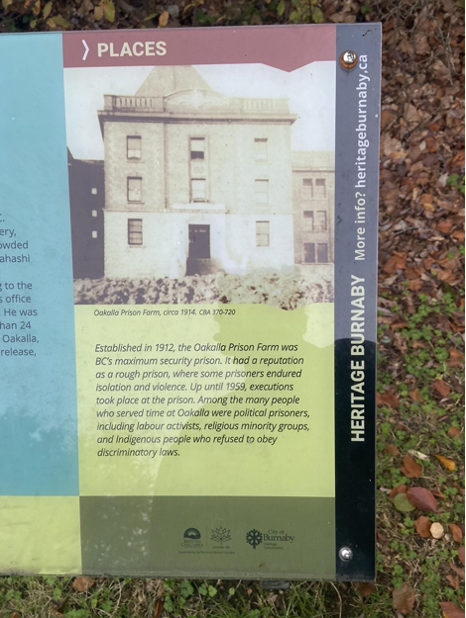

The Burnaby Village Museum, as part of the City of Burnaby’s reconciliation efforts, works closely with Kwantlen, Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh to give them access to stolen/lost cultural materials, and gets their help to create educational material such as the resource guide. There is even an Indigenous Learning House at the museum which is close to Deer Lake. Next to the Oakalla plaque, there is a newer informational plaque which talks about Japanese internment, and only briefly mentions Indigenous imprisonment (see image below). There is also a series of hard-to-see plaques on some of the stairs from the lake to the main road. However, these are hard to notice and you’d have to stop many times to get the full story which mentions Chief Capilano (even I have not read them all!). There should be more recognition of how the land was stolen and appropriated, and later used to imprison its own Indigenous people who lived there since time immemorial. A communication effort that includes Indigenous voices and expressions would be ideal. I would be open to contacting the City to start dialogue on this, though I recognize my position as a settler isn’t to speak for Indigenous peoples. There are bigger issues to use my privilege towards, such as advocating for housing equity, the opioid crisis, and self-governance. Through stories like the Oakalla prison, I am able to be on the landscape which is drastically altered from its pre-contact form, and reflect on the injustices which occurred not long ago. It helps me appreciate my own connection to the neighbourhood and how much it has changed. See a map below from the BVM guide of what Burnaby may have looked like long ago.

Sources

“Indigenous Peoples.” City of Burnaby, Burnaby Village Museum, 2017, www.burnaby.ca/City-Services/Planning/Social-Planning/Indigenous-Peoples.html.

Burnaby Village Museum. “Indigenous History in Burnaby”. (2019).

Oakalla images by Marina Miller 2020/19/12

“Indigenous Learning House.” Burnaby Village Museum, n.d., http://www.burnabyvillagemuseum.ca/EN/main/programs/by-series/school-programs/indigenous-learning-house.html