The urban landscape is built and weathered. It breaks down, is patched back up, or is left dilapidated. People, animals, and weather move across and through space, making their mark.

Either intentionally or by chance, things are dropped, lost, left, placed, made, created, and forced on urban space – adding to its entropy.

Think of a child’s toy dropped on the sidewalk; innocent colour perforating grey pavement, with an unknown story behind how it got there.

Eventually, we cross paths with one of these things, whether we’re on the way to the bus, or purposefully set out to see it. When we notice these out of place, artistic, or weird things, it can evoke emotion in us, and may even compel action.

In our fast-moving, structured cities, there is something remarkable in the little things that bring us pause. It isn’t something talked about in academia much because it’s generally perceived as mundane. But I think there’s something interesting here, and I am not the only one.

One of my best friends, Angelica, often posts out-of-place items and street art on her Instagram story, dubbed the “Lost in Transit” series. I’ve quietly appreciated them for a while.

I like to write about urbanism, and I realized Angelica’s thoughts could be the perfect medium to explore our kindred fascination for “street things”. I interviewed her on the phone, 7500 kilometers away from me, and it was truly wholesome.

“When you asked me, my jaw hit the floor. I just do it, and I wonder if anyone actually gives a shit that I’m doing this. And then you messaged me, and I was shocked, because someone actually noticing is crazy”.

Through her photos, people following Angelica can get a taste of what she feels when she encounters things in the city.

“When I see things like graffiti, or multiple bags of rice, chips, and cans of beans left at a bus stop, I wonder, ‘How did that get there? What is the story is behind it?’”

I wanted to explore why she is drawn to these things. She begins by recalling her youth.

“In high school I had ADHD, I could not focus, so oftentimes I would be just drawing and making little notes.”

“At the end of the year, everyone throws out their papers, but I would take mine home, and spend the first couple of weeks of summer going through all of the papers and cut out the little things that either my friends have written, little drawings I’ve done, or little headlines that stuck out.”

“To a normal person, they would be very easy to throw in the recycling bin, but to me they had little meanings.”

“I call myself a little crow because I have tons and tons of boxes of tiny little things that are considered junk… which technically makes me a hoarder!”

Going beyond paper and notes, and onto objects, her fascination converges with the urban landscape.

We can feel emotion when we see odd objects on the street, just as we feel when we see a very intentionally placed city-funded piece of art.

“Depending on the context, a little bit of sadness, melancholy, or a little pain.”

As I’ve previously argued regarding Metrotown, carefully planned out public art can be disappointing anyways.

Angelica cheekily agrees, “I will never forgive that fucking the Trans Am Totem, that was an insult. It made no sense. It was a $20,000 installation of some fucking cars, blocks away from one of the worst slums North America.”

We talk for a while about graffiti and street art, as it is a big portion of the photos Angelica takes. It is something which perforates an urban space designed to be clean and smooth.

“I have such a love and admiration for street art in general. In high school I looked up to many artists. To me that was “real art”, not what the art teacher was showing us.”

She elaborates, “It has an impact. A door that’s no longer in use, a wall that’s just empty and kind of boring. You’re taking this mundane, normal thing and putting a piece of yourself onto it, translating you into something physical that others can observe.”

Although she’s usually consuming other people’s street art, she does have some experience with the complexity of being the artist.

“As you know, I’m a hardened criminal with a one-day suspension for graffiti in grade 9.”

We laughed, reminiscing over this incident. At the time, I was furious at her for getting in trouble – I was averse to rebellion and hated seeing my best friend doing “bad” things.

Angelica’s infamous suspension on the final day of school arose because she was caught for repeatedly making paint-pen art in a bathroom stall.

She told the principal something which fascinates me, “If you didn’t cover it up the first time, I wouldn’t have done it over again.”

This attitude came from her love of making art, and perhaps part of that love was rebelling in the rigid space of our school system.

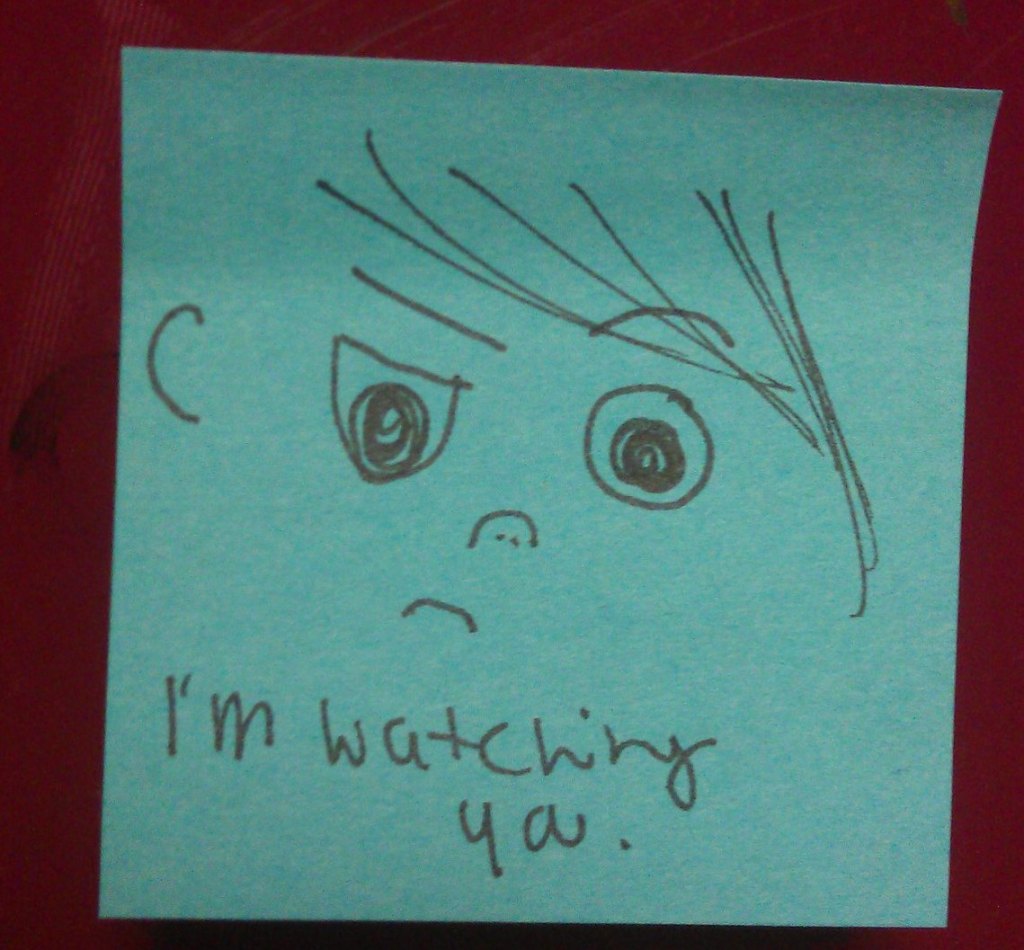

My favourite thing Angelica posts on her Instagram are tagged paint pen messages. They can be funny, thought-provoking, and deeply sad.

“I saw one downtown that said, RIP Fat Adam 2023. He may have been fat but so was his kindness… and I loved that. It was so simple and not artistic, but someone really felt compelled to put that down. He had an impact.”

“Any of the possible reasons people do this makes it interesting to me; to make you laugh, to confuse you, to make a statement, to piss you off. But regardless, someone put that there for a reason.”

In Vancouver, especially in marginalized communities like the Downtown Eastside, “public art [operates] as material and symbolic medium to (re)activate, remember and potentially hold space for conflicts about the meaning, presence and absence of diverse voices” (Landau-Donnelly, 2023, p. 14).

When things are intentionally enacted on urban space, in an unsanctioned way, I think it provides the area with character and culture that you can’t get from sanctioned art. As Hardwick puts it, referring to Vancouver, “If we do not look to the streets, we miss out on important thinkers” (Hardwick, 2017, p. 91).

One reason Angelica and I have been friends for 12 years, is we can talk about obscure stuff like this, energy unwavering.

“I find it hard to comprehend that everyone around me in public is having their own profound perceptions of life, their own struggles, and thoughts. I am not the main character on the Angelica show [laughs].”

“They’ve all grown up, loved, lost, struggled, and the things I capture remind me of this.”

“We are all here, trying to just get through it and experience it the best way we can, and I really respect people’s choices to leave little bits of themselves everywhere.”

Images by Marina

Beyond how things make her feel in the moment she encounters them, she takes pictures to “immortalize things that are not permanently there.”

This idea of lost objects moving in urban space is explored in depth by David Bissell (2009).

He talks specifically about the concept of lost clothing and describes the emotional experience of encountering them. We are all familiar with these – a lost mitten on the path, a pair of sneakers strung up on power lines, or a scarf tangled in tree branches.

I apply his logic to all the street things. Rather than being fixed and intentionally placed in an urban space, like a mural, a [street thing] is in a constant state of flux (Bissell, 2009, p. 96). This supports Angelica’s urge to immortalize things through photography.

When we see certain things in public, we wonder how they got there – this is also part of the emotional experience.

“Is this a kid who got a happy meal, it was the exact toy they wanted, it fell out of the car, and they’re gonna be super sad about it? Or was it like my sister and I, fighting over a toy, and my mom threw it out the window?”

Bissell argues that “the event of accidental loss demonstrates a movement of agency from the body to the object [itself]” (Bissell, p. 98). It now has a life on its own. And when Angelica, or me, or you take a picture of it or take it home, it becomes intertwined with a new body.

“The other day I found a ‘Little Miss Giggles’ toy. It was a little plushie with a keychain, and I was like wow, this is such a cute thing. How did he get here? I picked it up, put it in my pocket, and took it home.”

“In that moment, I’ve acknowledged it… it isn’t a forgotten piece of trash anymore… I’m attaching a human feeling to an object that doesn’t have a human feeling.”

In that statement, I think I found the essence of why we take things home. Personifying things, attaching emotion to it, is human nature. Some go as far to think it was the foundation of ancient religion (Hiebert, 2014, pp.5).

In a collective sense, all these experiences of seeing things on the street influences how we experience the city itself. For Angelica, it is an important part of enjoying the little things in life, and not becoming desensitized to the bustling, buzzing, and rushing of city life where beauty is often ignored.

To my surprise, she admits she seeks out these little things. She looks forward to seeing something interesting when she leaves the house.

It is amazing that emotion is caused by something that could have been absorbed and forgotten; an “enchanted materialism” when something spectacular emerges from the banal and mundane (Bissell, p. 104). Our encounters with objects in a sense gives it new life, even if only in our mind. Things that would inevitably “become woven tightly into the urban landscape” with decreasing visibility as they become weathered, are provided “the possibilities for new trajectories” when we intervene (Bissell, p. 108).

Images by Marina

Like Angelica, I also look out for things when I am walking. I feel compelled to capture photos. I call this “how I see neighbourhoods”, because it goes beyond art and objects. I like to capture interesting scenes or examples of urban planning and design, because I care about how people act upon cities.

Images by Marina

It is awesome having a camera in our back pockets. For the first time in history, fleeting moments, moving objects, and human oddities in the public realm can be immortalized.

This can be a good thing, but in moderation. Living in the most touristy city in the world, London, I see people with their phones out every day, looking through their screen rather than experiencing things through their eyes and hearts. Even I fall into this sometimes; I’m scared to lose the memory.

Whether I take a picture or not, I get a little spark when I see weird things outside. It makes me happy to be alive and around other people. It reminds me humans are just traveling in every direction, picking things up and dropping them down, crossing paths at all hours, all year. It is an infinite network of events which enacts upon the landscape, changing it, making it more unique, and affecting others.

Street things are a ubiquitous part of the urban human experience, and they ultimately “force us to think differently about the enactment of urban materialities” (Bissell, p. 96).

I love living in cities, and I am excited to see more weird and beautiful things next time I step out the door.

All images are from Angelica unless otherwise stated.

Sources

Bissell, D. (2009). Inconsequential materialities: The Movements of Lost Effects. Space and Culture, 12(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331208325602

Hardwick, J. (2017). Identity and survival in the multimedia art of street-involved youth. Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures, 9(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1353/jeu.2017.0013

A history of humans loving inanimate objects – pacific standard. Pacific Standard. (2014, February 21). https://psmag.com/social-justice/history-humans-loving-inanimate-objects-75192

Hood, S. B. (2002). Fire in the Streets: Vancouver’s public dreams make communal magic. Performing Arts & Entertainment in Canada, 34(1), 34–35. Landau-Donnelly, F. (2023). Ghostly murals: Tracing the politics of public art in Vancouver’s hogan’s alley. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 239965442311721. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544231172122

One thought on “Street things, and why they make us feel”