This is an excerpt from a school assignment. The whole group paper can be found on LinkedIn.

Human settlement in what is now called Lower Lonsdale goes back millennia. From both Oral Traditions and written accounts, we know about a couple of village sites in this area which existed before colonization.

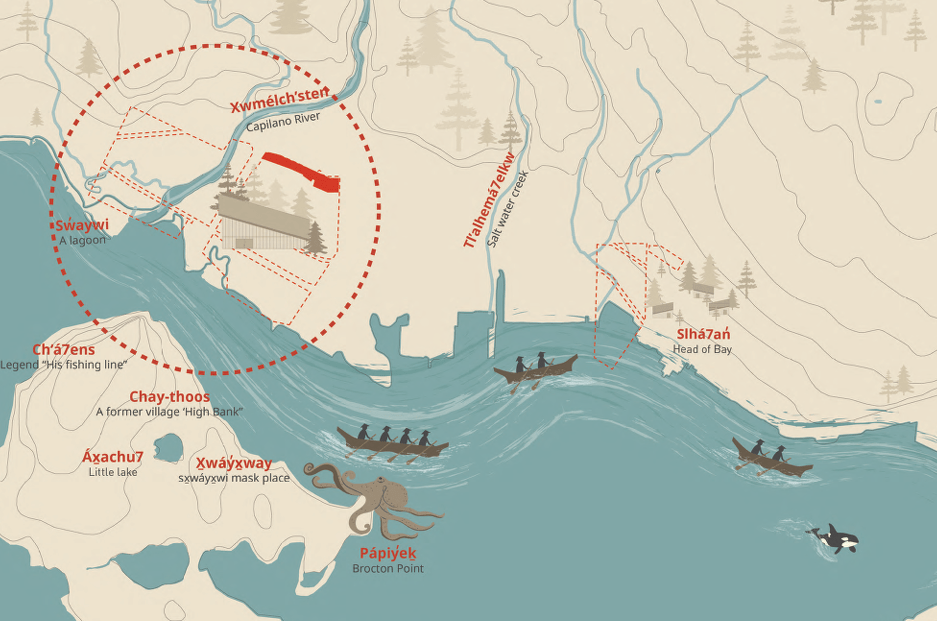

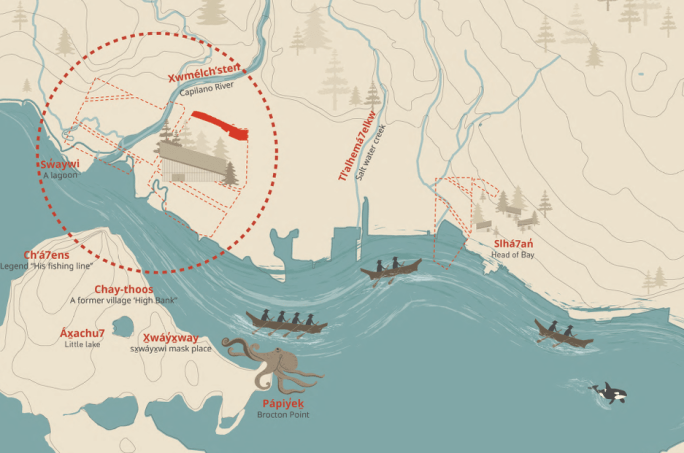

There were several hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh speaking peoples living in and around the North Shore since time immemorial, including Squamish. At the mouth of the Capilano River is a village site called X̱wemelch’stn (Homulchesan), a bit west of Lower Lonsdale.

Members of the Squamish Nation tell stories of a time here where the river was plentiful and the ecological system was in balance. It is remembered as a site of strength and cultural resilience, as well as a place where warriors would live and travel from.

The unique and cherished stories of this area help inform development and planning goals of the Squamish Nation to this day, like with a newly completed multi-generational housing development.

More directly on what is now Lower Lonsdale is another village site called Eslhá7an, meaning “head of the bay”. Established by the Squamish Nation, the settlement sat at the mouth of Mosquito Creek and along the surrounding mudflats. This would become Mission 1 Indian Reserve, including St. Paul’s Church, when settlers and the colonial government stole land for development and industry in the 1860s. The area now called The Shipyards was also a waterfront settlement shared by the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.

While there isn’t specific written information about the land use and density of the X̱wemelch’stn or Eslhá7an villages, we can make inferences based on our knowledge about Coast Salish life and settlement planning in the wider area. Lower Lonsdale Magazine describes the area as a “small Indigenous trading post” and an important trading hub. Their ample access to food resources set Coast Salish settlements apart from other Indigenous communities.

They had seafood, plants, seaweed, and game animals from the inlet, rivers, and mountains which allowed them to stay in place for months at a time or longer. Squamish families traditionally lived in multi-family longhouses. The Museum of North Vancouver shares a quote on their website that says, “when the tide goes out the table is set” when referring to this era.

Eslhá7an was a permanent village, but many residents moved around the region seasonally to visit family connections and follow certain foods and resources. This seasonal movement was common amongst Coast Salish communities.

Eurocentric concepts of planning don’t completely align with Coast Salish Traditional Knowledge, but we can assume their communities considered some of the perennial planning issues when establishing settlements. If we consider Eslhá7an, we can make some inferences to understand why there might have been a permanent village there:

Water supply: Being situated at the mouth of Mosquito Creek, there would be access to fresh drinking water.

Food: Salmon were abundant in the creek, and there was other seafood like shellfish in the tidal mud flats. People would also go up into the mountains to hunt and gather plants and rocks. Some of these campsites are now protected archaeological areas.

Safety: Floods may have been less of a risk compared to communities along the floodplain of the Fraser River, so Eslhá7an would be suitable from a natural hazards perspective. Many Indigenous settlements across North America were fortified for safety from other people, but Coast Salish log and plank house villages were often unfortified. When visitors came, there was a system for asking permission to stay or gather resources.

Need for connection: While the buildings may have been more permanent, people often moved seasonally to other villages and sites, and people would visit them as well. The form and allocation of land uses would have been set up to facilitate this seasonal movement, as well as social and spiritual practices.

Accommodating growth and change: Villages around the region ranged from dozens to hundreds, with some larger ones having over a thousand. Instead of using agriculture, they developed methods to preserve food, which sustained them through the seasons at such population densities. Coast Salish peoples used detailed Traditional Ecological Knowledge to survive on and preserve a vast territory for many generations. While colonial planning and development wouldn’t occur in Lower Lonsdale until the 1860s, there are documented interactions between the Squamish people and Europeans in the late 1700s. Colonists brought diseases like smallpox, which devastated the regional Indigenous population and beyond. This resulted in some surviving communities consolidating their settlements.

The City of Burnaby’s Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide is a useful reference which has some applicable Indigenous history concepts across Metro Vancouver. It explains that geography is often more important than chronology for understanding Indigenous histories. They can be told through physical features of the landscape, as well as the resources that those places provide.

Oral Traditions have brought these histories to the present, explaining both the origins of places like Eslhá7an and the continuing rights and connections people have to it. The nearby X̱wemelch’stn housing project is an example of how Squamish people are reimagining the traditional longhouse living practices on their traditional territory.

Sources

- ArcGIS StoryMaps. “The Shipyards: Then and Now.” February 13, 2023. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/a1e6c705d78b438d9c00edb4e2ad8355.

- ArcGIS StoryMaps. “Visions of the North Shore.” April 5, 2023. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f0f3b1dbcc93421599d4dd047e19d52d.

- “Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide,” Burnaby Village Museum. 2019. https://www.burnabyvillagemuseum.ca/assets/Resources/Indigenous%20History%20in%20Burnaby%20Resource%20Guide.pdf.

- “History of Lower Lonsdale and Moodyville in North Vancouver.” Lonsdale Avenue Magazine, March 11, 2023. https://lonsdaleave.ca/history-of-lower-lonsdale.

- “History – North Vancouver – North Vancouver Museum and Archives.” MONOVA, n.d. Accessed September 6, 2025. https://monova.ca/education/history/.

- Hodge, Gerald, David L. A. Gordon, and Pamela Shaw. Planning Canadian Communities: An Introduction to the Principles, Practices, and Participants in the 21st Century. Reprinted seventh edition. Northrose Educational Resources, 2025.

- “Our History.” Squamish Nation, n.d. Accessed September 6, 2025. https://www.squamish.net/about-our-nation/our-history/.

- Squamish Nation. Xwmelchsten Story of Place. 2024. https://www.squamish.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Xwmelchsten-Story-of-Place.pdf.

- Urban Arts Architecture. “Xwemelch’stn Multi-Generational Housing.” February 24, 2025. https://www.urban-arts.ca/news/2023/3/16/we-are-hiring-an-intern-architect-post-2-hng2c-ar9d3-x2js6-mms6m-caz3d.

- Urban Arts Architecture. “Xwemelch’stn Multi-Generational Housing.” Accessed September 7, 2025. https://www.urban-arts.ca/xwemelchstn-multigenerational-housing.